The Dominguez-Escalante Journal and Miera y Pacheco

The Dominguez-Escalante Journal, Their Expedition through Colorado, Utah, Arizona and New Mexico in 1776, edited by Ted J. Warner, translated by Fray Angelico Chavez and Miera y Pacheco; a Renaissance Spaniard in Eighteenth Century New Mexico by John L. Kessell

I am reviewing these two books together because they complement each other nicely given the overlap in time, key events and personalities. Bernardo Miera y Pacheco was cartographer of the expedition led by Fray Atanasio Dominguez and recorded by his junior colleague, Fray Francisco Velez de Escalante, that set out from Santa Fe, New Mexico in July 1776 searching for an overland route from Santa Fe to Monterrey, Alta California, but also looking for new mission and settlement fields for the Franciscan Order and the Spanish Crown.

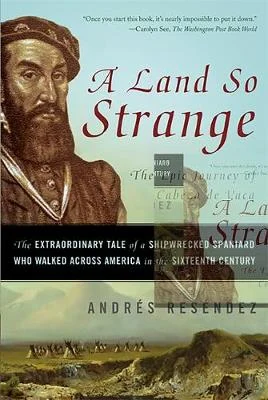

While ultimately unsuccessful in terms of its principal goal, reaching Monterrey, the very small Dominguez-Escalante expedition (15 men in all) was exemplary in terms of honorable treatment of the native peoples, description of their customs, lifestyles, linguistic affinities and appearance, as well as careful recording of geography, natural resources and settlement potential of the route travelled. In regards to good relations with the native peoples, this expedition ranks up there with the survival trek of Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca and his companions Dorantes, Maldonado and Estavanico two and a half centuries earlier.

For the first part of their journey, Dominguez and Escalante followed the route described in the journal of Juan de Rivera from his 1765 expedition, something I was unaware of. Rivera got as far as the Colorado River at Moab, Utah on a combined prospecting and reconnaissance mission at the behest of New Mexico governor Velez Cachupin.

Probably the foremost discovery made by the expedition was Utah Lake (their Timpanogos Lake). While there, they recorded the local’s description of a larger salt lake (the Great Salt Lake) in the next valley to the north, although they never visited it. They also encountered heavily bearded groups of Ute Indians, which they reasoned accounted for various accounts of a lost Spanish colony north of the Colorado River. They found a crossing of the Colorado River in Glen Canyon, now submerged, later used as part of the Spanish Trail, a route for trade between New Mexico and California, before hostilities with the Navajo made it impractical.

Bernardo Miera y Pacheco is mentioned a few times by name in the journal of the expedition. He went off by himself scouting a route without telling the rest of the party on August 16th. He was among those that dissented most strongly from the decision reached by the padres on October 8th to circle back to Santa Fe (versus continuing across the Great Basin looking for a route to Monterrey in mid-winter) and finally, he was berated for turning to a Paiute shaman for healing of a persistent stomach ailment on October 22nd , near the north rim of the Grand Canyon (I’d do the same under the circumstances!). However, in terms of concrete products of the expedition, his map rates right up with the journal as a useful and beautiful outcome. It was one of many maps he made in a long and colorful career in New Spain, starting in the city of Chihuahua, then the military outpost of Janos, on to El Paso del Norte and, finally, Santa Fe. In addition to cartographer, he was an amateur engineer, artist/santero responsible for several of the most celebrated retablos in New Mexico, a soldier, farmer and gov’t official. He was apparently well thought of and worked well with Tomas Velez Cachupin, Francisco Antonio Marin del Valle, Pedro Fermin de Mendinueta, and Juan Bautista de Anza; four of the most successful Spanish governors of New Mexico.

Much of the information for the northern marches of Spanish North America shown on Alexander von Humboldt’s landmark 1811 map of New Spain came from Miera’s map and the Dominguez-Escalante journal. On his 1804 visit to the US, Humboldt shared a draft of this map with Thomas Jefferson’s Secretary of Treasury, Albert Gallatin, and it may well have influenced the Jefferson’s views on further American expansion to the west and southwest. The Lewis and Clark expedition was already underway at this time to explore and establish a secure claim to the northwestern sector of the Louisiana territory recently purchased from France. The Humboldt map was copied by Gallatin and later loaned to the double agent and frontier schemer, Gen’l James Wilkinson. The latter gave it to Zebulon Pike who used it as the basis for his own “Map of the Internal Provinces of New Spain”.

I’d rate both books as excellent reads for those interested in the history and cartography of European exploration of the American West, as well as for fascinating insights into life in colonial New Mexico and the interaction amongst Europeans and Native Americans there and beyond.