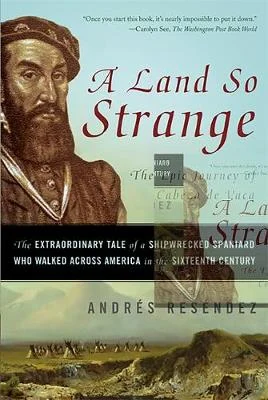

A Land so Strange

A Land So Strange: the epic journey of Cabeza de Vaca by Andres Resendez

This book is Resendez’ gloss on the most amazing survival story I know of, and I’ve read a lot of them! It’s not just amazing because three shipwrecked Spaniards and a Moor managed to make it from the Florida panhandle to the Gulf coast of Texas to the Pacific Coast of Mexico in a staggering eight year odyssey, but because of the unique way they did it, and the consequences for the Americas and the Spanish Empire.

The unfortunate Pánfilo de Narvaez, who was outsmarted and outfought by Cortez in the struggle for power during the conquest of Mexico, was able to get a license to explore, conquer and settle Florida (which was a generic name for what’s now the southeastern US) as a booby prize from the Spanish crown. His ill-fated expedition set off from Spain with 5 ships and 600 men in 1527. Amongst the crew were Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca, who served as expedition treasurer, Alonso del Castillo Maldonado, Andres Dorantes de Carranza and his Moroccan slave, Estevan. From the start, almost everything that could go wrong did go wrong. There were mass desertions in Hispaniola, the fleet was decimated by a hurricane in the Caribbean, the pilot was incompetent and ran the ship aground on shoals off of Cuba and then, to top things off, he didn’t know the currents of the Gulf of Mexico and instead of landing near the Rio de las Palmas in northeastern Mexico, they ended up 800 miles away in the Florida panhandle! Here Narvaez, down to 300 men, made a fatal error and split the expedition into sea and land contingents. The latter set off inland looking for kingdoms to plunder while the ships were supposed to meet them further up the coast. The land party found thatched villages whose wealth was in maize, which saved their lives, but no gold. The Spaniards were continually harassed and picked off by the natives as they struggled back to the coast, but never saw the ships again and decided to construct rafts and sail to Mexico. Down to 242 men, they set off to the west, along the coast, in three homemade craft. After a hellish journey, during which the raft carrying Narvaez disappeared, an estimated 80 survivors were cast away upon islands on the Texas coast during another storm.

Now things got really bad….the castaways lurched from one disaster to another trying to survive in the harsh environment of the Texas barrier islands. Some resorted to cannibalism, others died trying to head south to reach Mexico, while our four protagonists, who were by this time separated, were initially guests and then slaves of various local Indian groups. Cabeza de Vaca became a trader, able to do business amongst antagonistic tribes because he was a stranger. He travelled with his native band on its annual migration to harvest tunas (prickly pear cactus fruit) and it was there, four years after the shipwreck, that he was joyfully reunited with the other three survivors. They made a plan to escape and ultimately did, slipping away from their respective captors and moving off together toward the south and, they hoped, salvation in Mexico in 1534. Somewhere along the way, they discovered a talent for healing, using a combination of Christian prayer, primitive medical skills and, possibly, shamanistic ceremonies (CdeV describes a gourd filled with pebbles they used as their calling card and symbol of authority, very common amongst Native American healers) learned from host tribes. With this, they were transformed into the famous “Children of the Sun” and became part of a bizarre ritualistic exchange that is really what got them across the continent safe and sound. After performing their healings in a village, its inhabitants would take them to the next village along their route (to the west and northwest…why they turned and went this way instead of due south is still a bit of a mystery) where their hosts would trade them for everything owned by its poor occupants. They would heal the sick of this village, who would then take them on to the next one and repeat the process…so that the miraculous strangers flowed northwest and goods flowed back to the southeast and (presumably) everybody left happy.

Eventually they trekked up the Rio Grande to near its junction with the Conchos, and somewhere south of El Paso turned west and crossed the desert into the “corn belt” that stretched up from central Sonora into Arizona and New Mexico. There, sedentary villages had abundant supplies of corn, beans, squash and cotton as well as domestic turkey and wild game (including buffalo, hunted seasonally to the north, and deer). As they advanced, they began finding abandoned villages and hearing accounts of brutal white men on ferocious animals: the advance guard of Nuño de Guzman’s conquering army moving up the Pacific coast from Mexico City. They finally met Captains Cebreros and Alcaraz in 1536 on the Rio Petetlan in Sonora. As an interesting sidelight, they still had enough indigenous followers that 500 of them decided to stay on and found two villages there! They’d walked over 2,500 miles in two years and were described in one eye-witness account as having “hair down to their waists, beards to their chests, disheveled, with hats made of palm fronds, cloaks made of tanned deer hides with hair on them, barefoot, full of wrinkles, faces and hands burned by the sun, shorts made of sewn palm fronds”.

The repercussions of the four survivors of the Narvaez expedition’s miraculous re-appearance were almost immediate. They recounted their tale to Viceroy Mendoza in Mexico City, including reports they had gotten from their Indian hosts of multi-storied dwellings with abundant crops and, possibly, metals and gems, located to the north of their route. This rather meager second-hand story, compounded with the Aztec’s tale of an ancestral homeland called Aztlán, somewhere to the north or northwest of Mexico, accelerated Spain’s push in that direction. Mendoza commissioned Fray Marcos de Niza to follow up on the castaway’s tale, and gave him Estevan (given to him by Dorantes) as his guide. Estevan and Fray Marco’s “discovery” of Cibola/Zuni, where Estevan was killed in 1539, and Marcos’ wildly exaggerated description of the same, led almost immediately to the Vazquez de Coronado expedition of 1540, of which Mendoza was a heavy financial backer. All of this is quite ironic, given that the only “wealth” that Cabeza de Vaca, Dorantes and Maldonado actually saw with their own eyes on their journey consisted of a copper bell, 3 arrowheads made of “emerald” (more likely malachite, jade or some other green stone, as emeralds are non-existent in North America) and some beads described variously as of silver, coral or pearls! Quite a transfiguration from these meager things into the magnificent “Seven Cities of Cibola”!

Cabeza de Vaca began arguing for decent treatment of the Indians immediately upon being reunited with his countrymen in Sinaloa and continued to do so for the rest of his career. Conflicts with fellow colonists over just this issue ultimately landed him back in Spain in chains after a brief stint as governor of what is now Paraguay. I think he ranks up with Bernardo de las Casas as one of the most enlightened and humane Spaniards of the epoch and, together with de las Casas, probably ought to be canonized by the Catholic Church for this and his miracle-working trek !

Resendez adds some interesting commentary on Cabeza de Vaca’s chronicle, giving updated anthropological, ethnological and route information, plus background on the castaways, historical context and so forth, but by far the most powerful part of the book are the words of Cabeza de Vaca himself. In fact, I would recommend reading Resendez’ book only after having read Naufragos, either in translation or in the original Spanish. It is powerful.

The memory of the four castaways persisted for at least two generations in the southwestern US and northern Mexico, and future explorers reaped the benefits of their good relationship with the natives. Examples include Vasquez de Coronado, who was welcomed by an Indian family in the Texas panhandle that had known the castaways. They presented him with a pile of tanned buffalo hides, which his men proceeded to grab and divide amongst themselves leaving the Indians sad, as they had expected the Spaniards to bless them, as the castaways had done*. Antonio de Espejo led the third expedition into New Mexico in 1582 and was “received with joy and music” by the natives on the Conchos and Rio Grande because they were like the “Children of the Sun” who had passed through there over a generation before. Francisco de Ibarra’s expedition had the same experience with Querecho (Apache?) Indians near Paquime, Chihuahua in 1566. His chronicler, Baltasar de Obregon, relates that “they received the General with ceremonies like those of Paquime, used with Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca” and “because of their miracles and actions we were treated well”, “they said we were welcome in their lands as others who looked like us had passed through them many years ago and were the reason that their enemies had returned captives to them, they ordered the skies to rain on their lands, they cured and resuscitated the sick and the dead. They said and believed that we were Children of the Sun who they had feared, respected and adored as their god, and they affirmed that we had descended from heaven. They were continuously importuning us to touch and heal them which was the ceremony used by Cabeza de Vaca”.

I can heartily recommend this book to anyone interested in the early Eurpoean exploration of the Americas, survivor tales and those interested in pre-contact Indian culture and lifeways from coastal Texas, up the Rio Grande, across the Sierra Madre into coastal Sonora and Sinaloa.

*Amongst them was a girl who was “as white as a lady of Castille but she had her chin painted like a Moorish woman”. Hmmmmm.