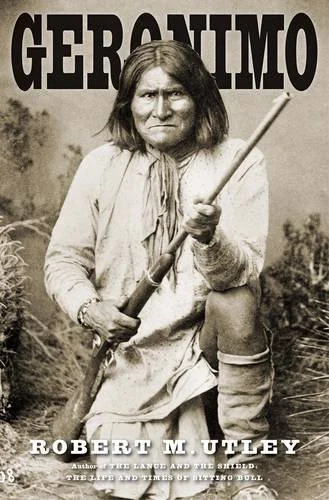

Geronimo

Geronimo by Robert M. Utley. Yale University Press, 2012.

Utley builds a compelling case that Geronimo, the historical American Indian with the highest name recognition worldwide today, was not a heroic native resistance leader, despite portrayals of him as such in much popular history, fiction and film of the last 60 years. He was a skilled warrior-shaman whose passions were raiding, plunder, his family and freedom. He treasured the traditional Apache life (which, by the way, involved lots of raiding and plunder) in his mountain homeland but was very adaptable and, above all, a survivor. He was not at all averse to stays on reservations, taking advantage of their relative security and free rations when it suited him, and he adapted well to his post-surrender status as a prisoner of war in exile from Florida to Alabama to Oklahoma. Opinion of him amongst his own people, both before and after his death, varied from admiration to mistrust and anger for the pain and suffering he caused Apaches in general with his breakouts, raids and the subsequent reprisals. Anglo newspapers in his day painted him as the devil incarnate, revisionist writers of our day as a folk hero.

Geronimo had some serious and consequential vices. These included an inordinate fondness of alcohol, whether traditional home-brewed maize beer (tiswin) or distilled spirits, a fondness shared with many of his people, and often taken advantage of by adversaries both Anglo and Hispanic. On many occasions, this led to disastrous and eminently avoidable debacles. He also tended to get over-confident and let his guard down when he crossed the border into Mexico, which led to several routs at the hands of his enemies. He was suspicious and distrustful of most everyone, he often lied to both whites and his own people and was both the source of, and very susceptible to, scurrilous rumors. He was also (and this was certainly not unique to Geronimo) extremely cruel on many of his raids and reprisal attacks, for although the Apaches did not rape or take scalps, they often did kidnap and torture.

Without delving into too much detail, I’ll highlight a few things I found particularly interesting in Utley’s book. Geronimo’s original name was Goyahkla, and he was born into the Bedonkohe band of the Chiricahua in 1823, somewhere on the upper Gila River, perhaps near modern Cliff, New Mexico or, alternatively, on the Middle Fork of the Gila, up by the Cliff Dwellings. The famous chief Mangas Coloradas, arguably the greatest of all Apache leaders (whose base was at Santa Lucia Springs, between Silver City and Cliff), was his mentor. Geronimo first appears in the Mexican records in 1843 and later participated in major battles there, including the great Apache victories at Galeana and Pozo Hediondo. Sonoran troops, on a reprisal mission for their defeat at the latter, killed his mother, wife and three children in a surprise attack outside of Janos, Chihuahua, fueling his hatred of Mexicans. Juh, Chief of the Nehdni band of the Chiricahua, whose base was in the Sierra Madre, was married to his sister (or cousin?) and was his closest ally. Geronimo’s first instinct whenever trouble threatened in the US was to head south and join him.

Utley marks Geronimo’s first documented appearance in Anglo-American history as a description by Lt. Joseph Sladen of the translator (Apache to Spanish) for Cochise in negotiations with General Howard at Apache Pass in 1872. The description matches him reasonably well, including the detail that he was wearing a shirt with the nametag of an officer killed in a battle the previous year in which Geronimo participated. In 1877, Indian Agent Clum arrested him at Ojo Caliente, New Mexico after a raiding binge and took him to the unhealthy* San Carlos, Arizona agency where he was jailed for three months. He fled San Carlos to raid in the US and Mexico thrice, in 1878, 1881 and 1885. Using Apache scouts, General Crook tracked him down in the Sierra Madre and got him to agree to return to the reservation in 1883, but Geronimo delayed months in honoring his word while he continued to pillage in Mexico. During his final breakout, he and his band of a few dozen followers eluded 5,000 US troops for a year. He negotiated with Crook but finally surrendered to the latter’s replacement, General Nelson Miles at Skeleton Canyon in the Peloncillo Mountains, on the Arizona-New Mexico border, on September 3, 1886, bringing to a close hundreds of years of Euro-American versus Indian wars.

Washington authorities decided that not just Geronimo’s band, but all 500 Chiricahuas, including the scouts that had helped track him down, their families and those uninvolved in his breakouts, were dangerous, and regardless of any promises that had been made to them, were to be treated as prisoners of war. So all were gathered up, put on trains and shipped to Fort Marion and Fort Pickens, Florida (where the "worst", including Geronimo, were incarcerated). They became instant tourist attractions for the locals. The Chiricahua stayed there until Herbert Welsh, leader of the Indian Rights Association, a pro-Indian lobby, visited them and then agitated in Washington for better treatment which resulted in most being relocated to Mount Vernon Barracks, north of Mobile, Alabama and Geronimo’s family being reunited with him at Fort Pickens. Finally, in 1888, all the Chiricahua (minus children sent to the Carlysle Indian School in Pennsylvania) were sent to Mt. Vernon Barracks. There, they were put to work farming, logging, building cabins etc., they made and sold crafts to tourists and were commended for their good behavior. Meanwhile they suffered from the awful climate and the diseases that came with it. Geronimo himself adapted well, gained back much of his old prestige and acted as disciplinarian for tribal youth, though his old traits of suspicion, lying, rumor-mongering and inconstancy occasionally re-emerged.

Finally, in 1894, in a decision driven by both the high mortality rate of the Chiricahua and the Army’s wish to close Mt. Vernon, Geronimo and his people were moved to a healthier climate at Fort Sill, Oklahoma (then still Indian Territory). There, Geronimo and his family farmed, he practiced traditional medicine and made forays to exhibitions and shows where he was the star attraction. He dictated his autobiography and converted to Christianity (Dutch Reformed Church) but never gave up his drinking and gambling. He contracted pneumonia after a drunken fall from his horse led to his spending a freezing night on the ground and died on February 19, 1909 at the age of 86.

In sum, his breakouts from the reservation and raids on both sides of the border took a terrible toll on his own people, the Chiricahua. Condemned with him as prisoners of war, they were exiled to unhealthy climes far from their homeland for 27 years before a remnant was finally resettled on the Mescalero reservation in New Mexico in 1913.

The best analogy I can summon up for Apacheria in the 19th C is Afghanistan of the early 21st C. The mountains of both were home to bands of bold, tough, independent tribes who gloried in raiding and plunder, and were experts at guerilla warfare. Unlike the Afghans, the Apaches had no unifying ideology (e.g. Islam) and faced not just a military occupation, but an invasion by a hostile numerically superior foreign population that was there to stay.

Utley’s bio of Geronimo is a worthwhile read, though I found a few minor geographical errors, and it fills in many lacunae in the histories of both the Chiricahua and Geronimo that remained from the previous two books (The Apaches by James Haley and Apaches at War and Peace: The Janos Presidio 1750-1858 by William Griffen) I read and reviewed. My only real quibble is Utley’s annoying trait of repeating slightly varied, or more or less detailed versions, of the same event twice in the book for who-knows-what reason, often confusing me as to whether he was talking about one event or two.

*Malaria was prevalent in the lower Gila River valley in the late 19th C.